Research

We study evolutionary biology, ecology, cultural evolution, behavior, and communication, using mathematical, computational, statistical, and AI models and collaborations with empirical biologists. Our interests span various biological systems, from viruses and microbes to cetaceans and hominids.

Our long-term goal is to understand how mechanisms that generate and transmit variation at different levels-genetic, behavioral, cultural-interact to shape the evolutionary process.

To get involved in our research, please email Yoav.

Current research interests

- Evolutionary Genetics and Genomics. We investigate adaptation mechanisms, including stress-induced mutagenesis, aneuploidy, and other genetic processes driving evolutionary change.

- Cultural Evolution. We explore the dynamics of cultural transmission, social learning, and the evolution of cooperation in humans and other animals.

- Computational and Statistical Modeling. We develop statistical and deep learning models to analyze (i) evolutionary and ecological experiments and (ii) anthropological and archeological data.

- Microbial Evolution and Ecology. We study microbial growth, competition, and adaptation in mixed cultures, focusing on ecological and evolutionary processes.

- Language and Communication. We examine the emergence and evolution of language structures and communication systems, including those of humans, other animals, and artificial intelligence.

Support

Our work is supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation (ISF), US–Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF), Templeton Foundation, Minerva Stiftung, Tel Aviv University Data Science Center, Safra Center for Bioinformatics, Amazon, and NVIDIA.

Our research

Evolutionary genetics

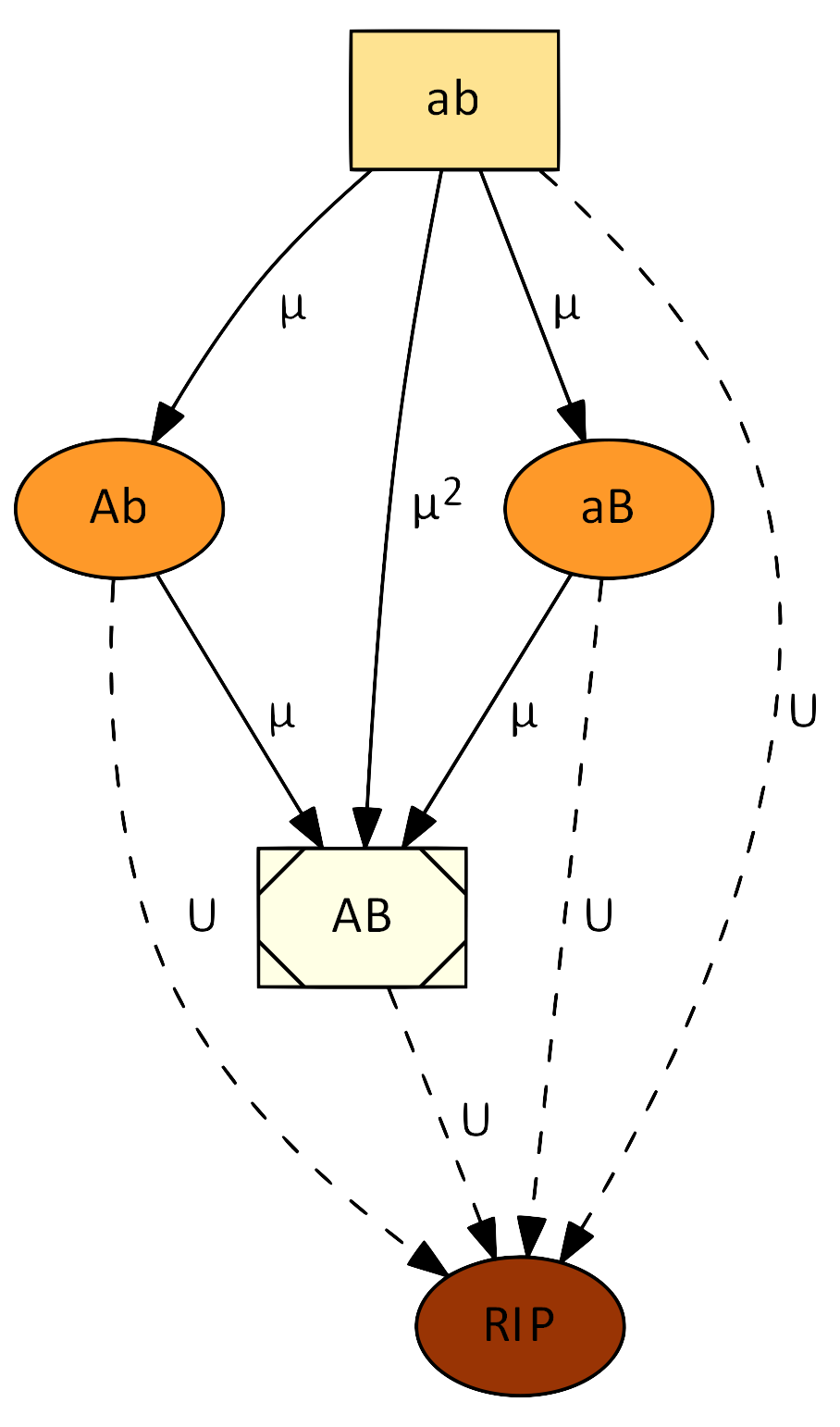

We developed a theoretical basis to explain the evolution of stress-induced mutagenesis – the phenomena in which stress induces a transient increase in mutation rates. Stress-induced mutagenesis is prevalent in bacteria and many eukaryote species, from yeast to human cancer cells. We used mathematical models and computer simulations to show that (i) stress-induced mutagenesis is favored by natural selection (Ram & Hadany 2012); that (ii) this is also true in the presence of rare recombination (Ram & Hadany 2019); that (iii) stress-induced mutagenesis increases the rate of complex adaptation without reducing the mean fitness of the population (Ram & Hadany 2014); and that (iv) errors in regulation of mutagenesis can be compensated by population communication (Dellus-Gur et al. 2017).

We have also found a general principle underlying this phenomenon, which we have termed the Modified Mean Fitness Principle (Ram et al. 2018). It determines that if below-average individuals generate more variation (be it genetic or phenotypic) than above-average individuals, then the population mean fitness will increase. The mechanisms for the generation of variation are not limited to mutation but rather may include dispersal (Gueijman et al. 2013), social learning, etc. We have also investigated how phenotypic switching of the mutation rate affects evolution (Lobinska et a. 2023).

In a project supported by NVIDIA and Amazon, we developed self-replicating artificial neural networks (SeRANNs), capable of copying their own genotypes and performing classification tasks that determine their reproductive success. We evolved 1,000 SeRANNs over thousands of generations and observed evolutionary phenomena such as adaptation, clonal interference, epistasis, and the evolution of mutation rates. Our findings demonstrate that universal evolutionary dynamics can naturally emerge in self-replicating models with implicit selection and mutation processes (Shvartzman and Ram 2024).

In a project funded by the ISF, we have studied the phenomnon of aneuploidy and copy number variation. We developed an evolutionary model to examine the role of aneuploidy in yeast populations under heat stress. Our findings suggest that while aneuploidy can provide immediate fitness benefits in stressful environments, it may act as an evolutionary diversion rather than a stepping stone, potentially delaying adaptation by hindering the fixation of more refined beneficial mutations (Kohanovski et al.). Next, we developed a mathematical model to assess how aneuploidy influences cancer cell populations under chemotherapy. Our findings indicate that aneuploidy can enhance tumor survival by increasing the likelihood of evolutionary rescue, particularly in smaller secondary tumors. This research underscores the significant role of chromosomal instability in cancer relapse following treatment (Stana et al.).

Cultural evolution

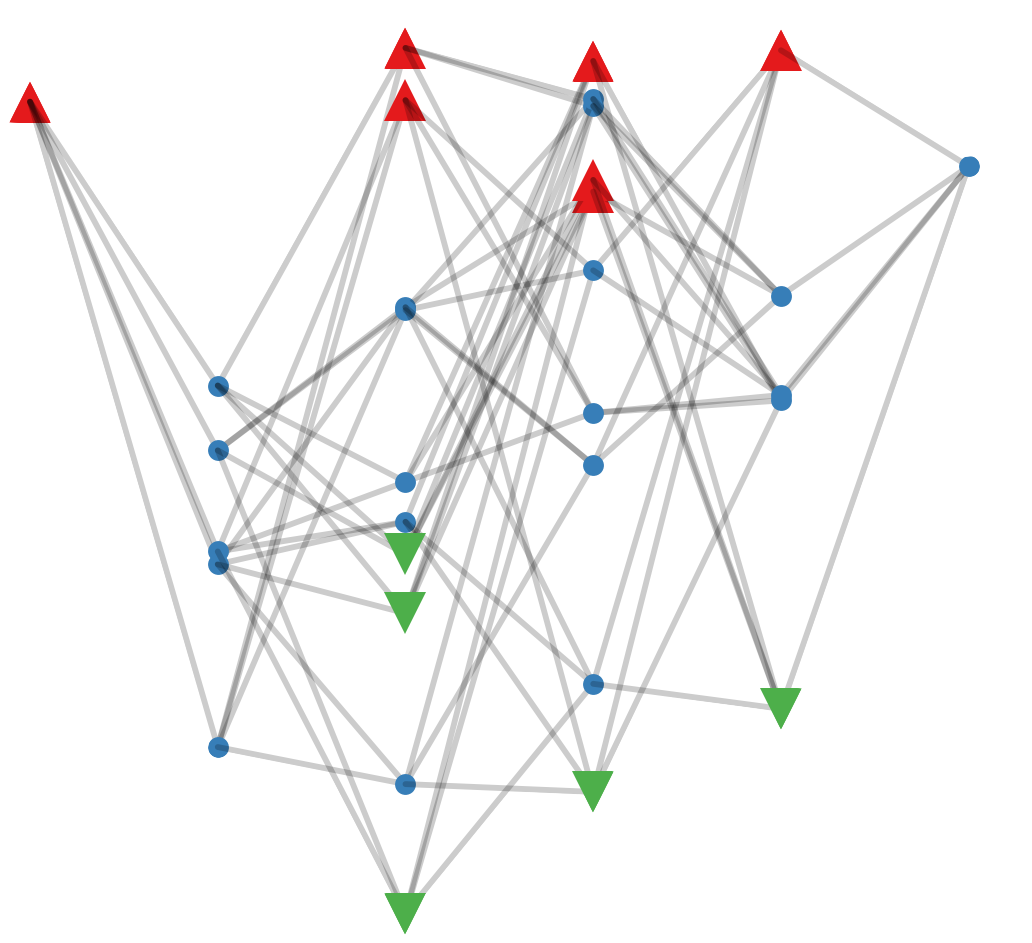

We studied the evolution of oblique transmission, in which offspring inherit their phenotype from a non-parental adult rather than their parents. This occurs primarily during social learning, but also in symbiont and pathogen transmission. We found that the evolutionarily stable rate of oblique transmission differs markedly from the rate that maximizes the geometric mean fitness of the population, implying a form ofprisoner's dilemma for social learning (Ram, Liberman & Feldman 2018). We've also studied how fluctuations in the rate of vertical vs. oblique transmission affect trait polymorphism (Ram, Liberman & Feldman 2019), what happens when the rate of vertical vs. oblique transmission depends on trait frequency (Liberman et al. 2019), or when transmission is biased towards to the more (or less) common phenotype (Denton et al. 2020), how such transmission biases affect cumulative culture (Denton et al. 2022), and how cultural evolution proceeds under prestige bias (Egozi and Ram 2024).

We also examined the evolution of cooperative behavior under non-vertical cultural transmission, focusing on the effect of assortment between cultural transmission and social interactions (Cohen et al. 2021), the effect of conformity and non-conformity (Denton, Ram & Feldman 2021), the emergence of cooperative hunting (Borofsky, Feldman & Ram 2024)

Recently, we analyzed datasets to identify four classes of cultural features and distinct clusters within Austronesian societies. We found varying modes of transmission and patterns of variation across these cultural classes, with geography alone insufficient to explain the observed diversity. Our results demonstrate how methods inspired by population genetics can effectively analyze cultural transmission and variation (Macdonald et al. 2024).

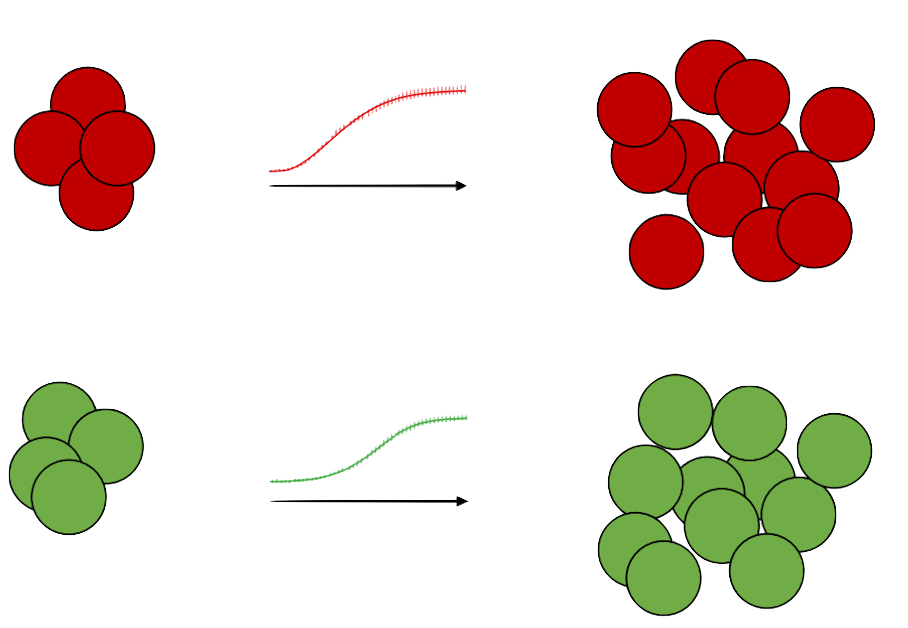

Analysis of evolutionary experiments

We developed and tested a new method for predicting growth in a mixed culture solely from growth curve data (Ram et al. 2019a, Ram et al. 2019b) in collaboration with the Berman lab at Tel Aviv University, Cooper lab at University of Houston, and with Marc Feldman and Lilach Hadany. We validated this method by performing growth curve and competition experiments with bacteria. Our new method not only results in a simple and cost-effective approach for estimating growth in a mixed culture and inferring competitive fitness but also provides information on the specific growth traits that contribute to differences in fitness, thus helping to bridge the gap between ecology and evolution.

We also collaborated with experimental microbiologists to analyze the results of evolutionary experiments. In experiments performed by the Kupiec lab at Tel Aviv University, haploid yeast cells frequently became diploid via two distinct genetic mechanisms. Using approximate Bayesian approximation (ABC), we estimated the rate of endoreduplication in these experiments and found that it was much higher than the mutation rate (Harari et al. 2018a, Harari et al. 2018b). In a project funded by the BSF with the Gresham lab at New York University, we inferred the formation rate and fitness effect of beneficial copy number variation mutations at a specific locus in yeast growing in a chemostat. This was performed using a state-of-the-art neural-network-based method, NPE, and evolutionary simulations (Avecilla et al. 2022; Chuong et al. 2024). We also applied this novel technique to estimate the mutation rate of the MS2 bacteriophage from evolutionary experiments together with the Stern lab at Tel Aviv University (Capsi et al. 2023).

COVID-19 pandemic

We used an SEIR model and MCMC parameter estimation to infer the effective start of non-pharmaceutical interventions (e.g., lockdowns) during the initial outbreaks of COVID-19 in 12 countries. We found that in the majority of cases, the effective start date is significantly different from the official and that this late effective start may lead to incorrect interpretation of the impact of interventions (Kohanovski et al. 2022).

We studied a model in which human behavior changes in response to the number of infected individuals causing the transmission rate to decrease. We found cycles, chaos, and high sensitivity to model parameters. This suggests that the predictive power of epidemiological models is hampered by complex human behavior (Arthur et al 2021; Stanford News).

We used evo-epidemiological models to examine the effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions (social distancing, lockdowns, etc.) and PCR testing on the evolution of virulence, attenuation, and test-evasiveness in SARS-CoV-2. We find conditions under which stronger measures select for less virulent strains, and more testing selects for less detectable strains, even if those strains are also less infectious (Gurevich et al. 2022).

Collaborators

Tel Aviv University

- Lilach Hadany

- Adi Stern

- Judy Berman

- Uri Liberman

- Uri Obolski

- Eli Geffen

- Yoni Belmaker

- Yossi Yovel

- Martin Kupiec

- Inon Scharf

- Uri Ben-David

- Amiyaal Ilany

- Shay Rotics

- Orr Spiegel

Elsewhere

- Marc Feldman, Stanford University

- David Gresham, New York University

- Tzachi Pilpel, Weizmann Institute of Science

- Oren Kolodny, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Shay Covo, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Shimon Harrus, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Tim Cooper, Massey University

- Daniel Weissman, Emory University

- Anna Selmecki, University of Minnesota

- Limor Raviv, Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics

- Lee Altenberg, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

- Lukas Galke, University of Southern Denmark

- Liran Samuni, German Primate Centre